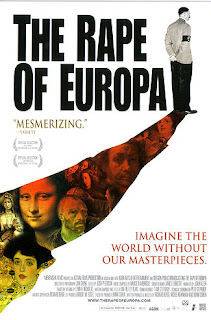

From 1933 until the end of the War the Nazis stole works of art in every country they captured. They took paintings, sculptures, gold, ceramics, religious objects, rare books and shipped them back to Germany. This systematic program of thievery is the subject of two films I've seen recently—The Monuments Men and The Rape of Europa.

The Monuments Men is George Clooney’s semi-fictional account of a group of men, an odd bunch at that, who recovered some of the most revered works of art stolen by the Nazis. We meet the men, are shown some of the art treasures they seek and eventually find, deep in a mine in Germany. We learn about the efforts of the museums in Paris, Italy, and Russia to remove the works from the museums and attempt to hide them in the countryside. And we meet Hitler, Goring and their henchmen who directed the Nazi looting organizations.

The Rape of Europa is a much more thorough documentary of the art works confiscated by the Germans. It’s a vast subject and the film attempts to sample a fair number of the them, including the conflict allied commanders faced in attacking a setting that was of artistic and historical significance, as well as the lengthy post war recovery efforts

One by one most of the treasures were found in over 1,000 places in Germany and Austria. Still an estimated to be 20% of the artworks stolen by the Germans have never been recovered, hidden away somewhere or destroyed by the Nazis.

From time to time we hear about a cache or a particular work that has finally been discovered. Recently hundreds of works, including paintings by Picasso and Matisse, confiscated by the Nazis were discovered in an apartment in Munich that belonged to an elderly German.

Earlier a museum in Salt Lake realized that a small, pastoral painting by the French artist Francois Boucher was part of a collection stolen by the Nazis from a Jewish art dealer. Once confirmed, the museum returned the painting to the dealer’s daughter without reservation. And so the trail to the stolen art goes on to this day. Doubtless some will never be found.

However, neither movie discusses the millions of books stolen or destroyed by the Nazis, largely books confiscated from Jewish libraries throughout Europe. Starting with the book burnings of May 1933, the Nazis knew well how critical books were to the Jews. While most of them were destroyed, many that were valuable in some way were saved and sent to libraries or private collections in Germany.

The scope of Nazi book looting was enormous and the Monuments Men were able to return the majority of the books to their owners. Still a great many of the estimated two and a half million books they found could not be returned to their owners either because there was no way to identify them or their owners were no longer alive.

3.31.2014

3.27.2014

David and Goliath

Malcolm Gladwell seems to have mellowed a bit in his recent book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits and The Art of Battling Giants. There are fewer certainties or broad generalizations and far more “sometimes” and “in this kind of situation.”

For the first time in my memory, Gladwell acknowledges the limits his stories. They are the surprises, the unexpected that upsets myths. And like all his other books, the stories he tells are amusing and suggest novel ways to understand them.

Consider individuals who are dyslexic and have extreme difficulty reading. Can you imagine becoming a lawyer if you have dyslexia, getting through those enormous law book tomes, case after case of dense, complex details and interpretations? Gladwell discusses David Boies, who is dyslexic and in spite of that one of the leading lawyers in this country who represented IBM and Microsoft against US government prosecutions, Al Gore in Gore vs. Bush in the 2000 Presidential election and many other major legal cases.

Gladwell’s interpretation of Boies success represents the theme of this book: How persons with a disadvantage learn how to compensate for them, often enabling them to outperform or at least perform as well as those who have all the advantages. In Boies case, he learned to read more carefully, to listen intently, asking questions and to practice arguing cases.

Gladwell admits that compensation learning is really hard but if it is attempted intensely it can lead to skills that becomes habitual. Having a disadvantage need not always restrict someone. The qualities that appear to give a person “strength are often the sources of great weakness, whereas for the weak, the act of facing overwhelming odds produces greatness and beauty.”

Similarly, Gladwell weaves together stories of how a girls basketball team overcame their weakness by applying the full court press, how in 1917 the vastly outnumbered Arabs, led by T.E. Lawrence defeated the Turks stationed by Aqaba by attacking them from the desert, rather than the sea, as expected. Crossing the desert with such a small band of troops was “so audacious that the Turks never saw it coming.”

“T.E. Lawrence could triumph because he was the farthest thing from a proper British Army officer. He did not graduate with honors from the top English military academy. He was an archaeologist by trade who wrote dreamy prose.”

Gladwell calls into doubt the belief that small classes are better than larger classes, that well-endowed private schools, attended by wealthy students are better than less privileged state run schools, and that losing a parent as a young child limits career achievements. Consider this remarkable observation:

“Of the 573 eminent people for whom Eisenstadt could find reliable biographical information, a quarter had lost at least one parent before the age of ten. By age fifteen, 34 percent had had at least one parent die, and by the age of twenty, 45 percent.” See Note Below

David and Goliath repeats this theme over and over with entertaining tales, drawn across a wide spectrum. Disadvantages are not always limiting, weaknesses can be overcome, the unexpected can triumph, and “in certain circumstances a virtue can be made of necessity.” Gladwell clearly enjoys telling these stories and the reader enjoys knowing about them, but he is not writing science. Instead, he is piecing together a montage from disparate fragments of evidence.

Note:

Recently there has been some discussion of this topic. On the NPR Web site, Robert Kruwich asks, Why are there so many of them?

He cites evidence drawn from several sources, largely case studies. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor lost her father when she was nine. Bill de Blasio, mayor of New York, lost his father when he was eighteen.

Gladwell also points out that almost a third of the US Presidents lost their fathers when they were young. A psychologist claims that prisoners are two to three times more likely to have lost a parent when they were young than the population as a whole.

Note the reasoning here. None of it has anything to say about individuals who didn’t lose either parent when they were young. A sizable majority of children are raised in two parent families. Are they any less successful that those who aren't? The answer to that question is essential before we can claim the relationship between childhood parental loss and adult achievement is significant.

Two thirds of American Presidents did not lose one or both of their parents when they were young. I am sure the same can be said of the Justices on the Supreme Court and the majors of the major cities of this country.

Nor can we attribute any causal relationship between childhood parental loss and adult success. Perhaps children learn adaptive strategies for dealing with the loss of a parent. Sotomayor comments that, “the only way I’d survive was to do it myself.” And De Blasio, whose father was an alcoholic, like Sotomayor’s, says, “I learned what not to do.”

Countless factors lead to adult success, some of which we know a little about, others remain unknown, including the matters of chance and luck. While the incidence of parental death or absence seems high among successful individuals, its meaning must be weighed against the far larger incidence of the success of children raised in two parent families.

3.24.2014

Roth on Roth

Yes, character is destiny, and yet everything is chance.

Last week Philip Roth celebrated his 81st birthday. What is he up to these days? As far as we know, he’s holding firm to his claim that his writing days are over. On the other hand, his interview days are moving briskly along. The most recent is one he gave to an editor at the publisher of the Swedish translation of Sabbath’s Theater. (Reprinted in the Sunday Times Book Review, 3/2/14)

Whatever else he is doing, Roth has lost none of his verbal intensity, energetic prose, passionate expression, forceful phraseology, dynamic voice, dramatic discourse, pyrotechnic style, explosive language, not any of it. Examples:

In reply to a question about the subject of Sabbath’s Theater, he said:

I could have called the book “Death and the Art of Dying.” It is a book in which breakdown is rampant, suicide is rampant, hatred is rampant, lust is rampant. Where disobedience is rampant. Where death is rampant.

In reply to another on the claim he is misogynistic Roth replied:

Misogyny, a hatred of women, provides my work with neither a structure, a meaning, a motive, a message, a conviction, a perspective, or a guiding principle.

He disagreed with those who say his books focus on masculine power, rather, he said they deal with it’s antithesis: “masculine power impaired”:

The drama issues from … men who are neither mired in weakness nor made of stone and who, almost inevitably, are bowed by blurred moral vision, real and imaginary culpability, conflicting allegiances, urgent desires, uncontrollable longings, unworkable love, the culprit passion, the erotic trance, rage, self-division, betrayal, drastic loss, vestiges of innocence, fits of bitterness, lunatic entanglements, consequential misjudgment, understanding overwhelmed, protracted pain, false accusation, unremitting strife, illness, exhaustion, estrangement, derangement…

Finally, when asked how he views contemporary culture, he let loose with this one:

Very little truthfulness anywhere, antagonism everywhere, so much calculated to disgust, the gigantic hypocrisies, no holding fierce passions at bay, the ordinary viciousness you can see just by pressing the remote, explosive weapons in the hands of creeps, the gloomy tabulation of unspeakable violent events, the unceasing despoliation of the biosphere for profit, surveillance overkill that will come back to haunt us, great concentrations of wealth financing the most undemocratic malevolents around, science illiterates still fighting the Scopes trial 89 years on, economic inequities the size of the Ritz, indebtedness on everyone’s tail, families not knowing how bad things can get, money being squeezed out of every last thing — that frenzy — and (by no means new) government hardly by the people through representative democracy but rather by the great financial interests, the old American plutocracy worse than ever.

Philip Roth is the same old robust Philip Roth. He’s lost none of his power and says at last, he is as free as a bird, one released from the cage of writing novels.

Last week Philip Roth celebrated his 81st birthday. What is he up to these days? As far as we know, he’s holding firm to his claim that his writing days are over. On the other hand, his interview days are moving briskly along. The most recent is one he gave to an editor at the publisher of the Swedish translation of Sabbath’s Theater. (Reprinted in the Sunday Times Book Review, 3/2/14)

Whatever else he is doing, Roth has lost none of his verbal intensity, energetic prose, passionate expression, forceful phraseology, dynamic voice, dramatic discourse, pyrotechnic style, explosive language, not any of it. Examples:

In reply to a question about the subject of Sabbath’s Theater, he said:

I could have called the book “Death and the Art of Dying.” It is a book in which breakdown is rampant, suicide is rampant, hatred is rampant, lust is rampant. Where disobedience is rampant. Where death is rampant.

In reply to another on the claim he is misogynistic Roth replied:

Misogyny, a hatred of women, provides my work with neither a structure, a meaning, a motive, a message, a conviction, a perspective, or a guiding principle.

He disagreed with those who say his books focus on masculine power, rather, he said they deal with it’s antithesis: “masculine power impaired”:

The drama issues from … men who are neither mired in weakness nor made of stone and who, almost inevitably, are bowed by blurred moral vision, real and imaginary culpability, conflicting allegiances, urgent desires, uncontrollable longings, unworkable love, the culprit passion, the erotic trance, rage, self-division, betrayal, drastic loss, vestiges of innocence, fits of bitterness, lunatic entanglements, consequential misjudgment, understanding overwhelmed, protracted pain, false accusation, unremitting strife, illness, exhaustion, estrangement, derangement…

Finally, when asked how he views contemporary culture, he let loose with this one:

Very little truthfulness anywhere, antagonism everywhere, so much calculated to disgust, the gigantic hypocrisies, no holding fierce passions at bay, the ordinary viciousness you can see just by pressing the remote, explosive weapons in the hands of creeps, the gloomy tabulation of unspeakable violent events, the unceasing despoliation of the biosphere for profit, surveillance overkill that will come back to haunt us, great concentrations of wealth financing the most undemocratic malevolents around, science illiterates still fighting the Scopes trial 89 years on, economic inequities the size of the Ritz, indebtedness on everyone’s tail, families not knowing how bad things can get, money being squeezed out of every last thing — that frenzy — and (by no means new) government hardly by the people through representative democracy but rather by the great financial interests, the old American plutocracy worse than ever.

Philip Roth is the same old robust Philip Roth. He’s lost none of his power and says at last, he is as free as a bird, one released from the cage of writing novels.

3.20.2014

On Leaving Home

James Wood, who teaches literary criticism at Harvard and on occasion reviews books for the New Yorker, was born in Durham, England. He has lived in the United States for 18 years and says he never expected to stay this long. He writes about his ambivalence at living here, on what it means to return to his home that still feels like Durham, and the strange sense of exile he feels in this country. (Times Literary Supplement 2/20/14)

When he came to the United States, he had no sense of what might be lost. To lose a country or a home is “an acute world-historical event, forcibly meted out on the victim, lamented and canonized in literature and theory as exile or displacement…It is the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home: its essential sadness can never be surmounted.”

While I have often written about my search for a home, a Querencia in the Spanish sense of the world, I’ve never experienced anything like the sense of exile Wood describes or the more extreme exile that a person must feel when they leave the country of their birth, either intentionally or by force, for a place where they don’t know the language or a single person.

And I’ve always known I would return to the place I left, even if it didn’t feel like home or the home I was searching for. And I never felt the sense of homesickness discussed by Wood when he says he is sometimes homesick as he longs for Britain. “It is possible, I suppose to miss home terribly, not know what home really is anymore and refuse to go home, all at once. Such a tangle of feelings…”

He says he has made a home in the United States “but it is not quite Home.” Wood says so much has disappeared from his life, the English reality that he craves, the English voice, the peculiar English phrases and puns. All of that is but a memory and he confesses he knows little anymore about modern life in England. “There’s a quality of masquerade when I return, as if I were putting on my wedding suit, to see if it still fits.”

After reviewing the works of authors who have written about exile—Edward Said, Geoff Dyer, W. G. Sebald, Teju Cole—Woods concludes by returning to the time, 18 years ago, when he left England. Then he had no idea how it would “obliterate return.” “What is peculiar, even a little bitter, about living for so many years away from the country of my birth, is the slow revelation that I made a large choice a long time ago that did not resemble a large choice at the time…”

Isn’t this true of many of the decisions we have made throughout our life? We are woefully deficient in predicting how we will feel about the decisions we make and often only become aware of what we have done long after the choice was made, when it’s too late to do anything about it, should we wish.

When he came to the United States, he had no sense of what might be lost. To lose a country or a home is “an acute world-historical event, forcibly meted out on the victim, lamented and canonized in literature and theory as exile or displacement…It is the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home: its essential sadness can never be surmounted.”

While I have often written about my search for a home, a Querencia in the Spanish sense of the world, I’ve never experienced anything like the sense of exile Wood describes or the more extreme exile that a person must feel when they leave the country of their birth, either intentionally or by force, for a place where they don’t know the language or a single person.

And I’ve always known I would return to the place I left, even if it didn’t feel like home or the home I was searching for. And I never felt the sense of homesickness discussed by Wood when he says he is sometimes homesick as he longs for Britain. “It is possible, I suppose to miss home terribly, not know what home really is anymore and refuse to go home, all at once. Such a tangle of feelings…”

He says he has made a home in the United States “but it is not quite Home.” Wood says so much has disappeared from his life, the English reality that he craves, the English voice, the peculiar English phrases and puns. All of that is but a memory and he confesses he knows little anymore about modern life in England. “There’s a quality of masquerade when I return, as if I were putting on my wedding suit, to see if it still fits.”

After reviewing the works of authors who have written about exile—Edward Said, Geoff Dyer, W. G. Sebald, Teju Cole—Woods concludes by returning to the time, 18 years ago, when he left England. Then he had no idea how it would “obliterate return.” “What is peculiar, even a little bitter, about living for so many years away from the country of my birth, is the slow revelation that I made a large choice a long time ago that did not resemble a large choice at the time…”

Isn’t this true of many of the decisions we have made throughout our life? We are woefully deficient in predicting how we will feel about the decisions we make and often only become aware of what we have done long after the choice was made, when it’s too late to do anything about it, should we wish.

3.17.2014

"Her Radar Was Always On"

In a moving tribute to his mother, Andre Aciman describes (New Yorker (3/17/14) her as beautiful, everyone thought so too. He says she was also vibrant, spirited, funny sometimes. She was born in Egypt, sent to a special school in France by her Jewish parents, well mannered with many friends.

She was also totally deaf as a result of meningitis as a child. There is no cure for it and she became deaf when the disease affected that part of her brain responsible for hearing. How she managed the rich life she lived borders on the miraculous to me.

She never learned more than a rudimentary skill at sign language and while she spoke, it was with a monotone, guttural voice that most people could hardly understand. They were more likely to laugh and make fun of her. She shrugged it off and sometimes laughed along with them.

But she did learn to read and write, although Aciman says she wasn’t able to form general concepts or understand abstract vocabulary. But she compensated for being deaf by her vivacious personality “her warmth, her unusual mixture of meekness and in-your-face boldness.”

Aciman’s family fled Egypt, along with a great many other Jews, shortly before the start of the Second World War. They settled in Italy for a while and then migrated to this country. But she never was able to master English, as well as she had French or Greek. But like deaf people often do, she pretended that she did and mumbled something in exchange that was usually understood, although she was never sure.

The various ways the deaf try to deal for their condition interests me greatly as I no longer hear as well as I once did. She carefully watched the lip movements of those she spoke to, as well as their gestures, her perception of their warmth, closeness, smile or frown, and all the other cues we normally use, often without realizing it, in observing someone’s body language.

With the increasing versatility of digital forms of communicating, Aciman dreamed of some device that would enable his mother to communicate more readily with her friends. When she was in her mid-80s, he gave her an iPad. She took to it immediately (in her 80s, no less!) and would Skype and FaceTime her friends, some of whom she hadn’t seen for years.

Aciman believes his mother was among the most discerning, perceptive persons he has known. She didn’t need language and was able to communicate in ways all of often use, again without being aware of it. But it gave her a life, a life that Aciman points out and, as I have come to appreciate more and more, is sometimes more direct, more telling. He concludes:

“Now that I think of what Shakespeare might have called her “unaccommodated” language, I realize how much I miss its immediate, tactile quality, from another age, when your face was your bond, not your words. I owe this language not to the books I read or studied but to my mother who had no faith in, and no latent or much patience for, words.”

She was also totally deaf as a result of meningitis as a child. There is no cure for it and she became deaf when the disease affected that part of her brain responsible for hearing. How she managed the rich life she lived borders on the miraculous to me.

She never learned more than a rudimentary skill at sign language and while she spoke, it was with a monotone, guttural voice that most people could hardly understand. They were more likely to laugh and make fun of her. She shrugged it off and sometimes laughed along with them.

But she did learn to read and write, although Aciman says she wasn’t able to form general concepts or understand abstract vocabulary. But she compensated for being deaf by her vivacious personality “her warmth, her unusual mixture of meekness and in-your-face boldness.”

Aciman’s family fled Egypt, along with a great many other Jews, shortly before the start of the Second World War. They settled in Italy for a while and then migrated to this country. But she never was able to master English, as well as she had French or Greek. But like deaf people often do, she pretended that she did and mumbled something in exchange that was usually understood, although she was never sure.

The various ways the deaf try to deal for their condition interests me greatly as I no longer hear as well as I once did. She carefully watched the lip movements of those she spoke to, as well as their gestures, her perception of their warmth, closeness, smile or frown, and all the other cues we normally use, often without realizing it, in observing someone’s body language.

With the increasing versatility of digital forms of communicating, Aciman dreamed of some device that would enable his mother to communicate more readily with her friends. When she was in her mid-80s, he gave her an iPad. She took to it immediately (in her 80s, no less!) and would Skype and FaceTime her friends, some of whom she hadn’t seen for years.

Aciman believes his mother was among the most discerning, perceptive persons he has known. She didn’t need language and was able to communicate in ways all of often use, again without being aware of it. But it gave her a life, a life that Aciman points out and, as I have come to appreciate more and more, is sometimes more direct, more telling. He concludes:

“Now that I think of what Shakespeare might have called her “unaccommodated” language, I realize how much I miss its immediate, tactile quality, from another age, when your face was your bond, not your words. I owe this language not to the books I read or studied but to my mother who had no faith in, and no latent or much patience for, words.”

3.13.2014

The Girl in the Blue Beret

Whatever we did, regardless of the risk, we had to do it. For my parents, it was automatic. For me also. We simply did it…Not every Frenchman had taken such chances.

The Second World War continues to preoccupy me. It isn’t entirely clear why. Partly I think it is the courage displayed, the resistance in France, the Holocaust, those who helped the Jews and those who didn’t. As a child I lived through the early part of the war in a house by the sea in Los Angeles. We worried about a Japanese invasion.

My reading isn’t focused or concerned with particular historical event or person. Rather, I chance upon news of an interesting book and begin reading it. So it was with an article, “The Real Girl in the Blue Beret,” that Bobby Ann Mason posted on the New Yorker Web site. She was writing a book about a downed American pilot who is rescued by members of the French Resistance, one of whom was a teenager wearing a blue beret

She wrote this woman in the hopes of meeting her, not know if she was still alive. Yes, she was, now well over 80, but still full of life and willing to talk about her experiences during the war. That is how I came to read Mason’s novel and how she transformed the wartime experiences of the aviator and the young resistance member into a work of fiction.

Marshall Stone is a retired American airline pilot who returns to France to meet the people who helped him cross over the Pyrenees and return to his bomber group in England. Annette is the teenage resistance fighter who was instrumental in his escape. Eventually he finds her, they unfold their respective histories, strike up a close relationship, and Marshall’s attempt to recapture this crucial part of his past comes full circle.

In the end, Annette answers the question I pose about every rescuer I read about:: Why did they incur such risks?

Whatever I did for you, I also did for myself, for my family, for France. We were crushed, Marshall. Defeated. You cannot know the shame. Whatever any of us did, we did for ourselves—so that we could have still a little self-respect. Just a little.

3.10.2014

Deborah Eisenberg

Deborah Eisenberg speaks of writing as something she has to do in her recent Paris Review (Spring 2013 #218) interview. “But really, one writes to write.” She doesn’t think of it as therapeutic, but then she says she couldn’t have managed the despair she was experiencing, if she hadn’t started to write.

She is bothered by how difficult it is and but doesn’t want it to be easy or approached casually. “I want to do something that I can’t do. I want to be able to do something that I am not able to do.” How often do we hear someone saying this sort of thing?

No wonder she is so often in despair and that for months, perhaps, years, she can’t write anything that satisfies her.

Eisenberg is Jewish, although not spiritually so, for whom Holocaust remains a haunting presence. And like her, I have sought to learn more about it from those who suffered through it or were able somehow to survive. She comments:

“I remember once when I was about five, asking my maternal grandfather, What was it like where you came from? And he said, It was cold. That was the end of the conversation. America was the beginning as far as many of those immigrants were concerned. What happened before that stayed in the darkness.”

“Many of us grew up knowing nothing, or next to nothing, about the horrors of grandparents lived through, and when we search for the source of certain anxieties, all we can locate is a kind of blank inscrutability.”

She is asked about the disparity between her life and that of poverty-stricken individuals. She replies: “The way to respond is to be as much of an activist as you can be, in whatever way you can be.”

It is a noble goal, but she is silent on how she goes about that. Again, I share her belief, but do nothing but proclaim the virtues of doing something.

She says what makes writing worthwhile is knowing you have a reader, one who responds as if they heard you. After all, writing is rather like communicating. You want to dialogue with someone.

Eisenberg concludes her interview with this comment about her writing life: “Either you have to quit for good or you have to tough it out. That’s the choice. You have to be patient.”

Yes, be patient, Richard. If you have anything left, it will come to you and if doesn’t, it will be all right.

3.06.2014

The Walking Desk

I’ve been exercising for years, was a long-time runner, now I go to the gym everyday. Or when I’m out of town, I take a walk, often two or three a day. The rest of the day I sit at my desk. That means I’m sitting most of the time I’m awake. Not good.

In an article in the New Yorker, the always-amusing Susan Orlean claims that sitting most of the day can cancel all the benefits of exercising for an hour or so of daily exercising. I always thought that being fit and healthy was simply a matter of frequent exercising. No, she says, non-exercise activity is far more important.

Here she is writing the article while walking slowly on a treadmill, typing away on her “walking desk.” The treadmill sits below an elevated platform with her computer screen and keypad, printer (on the floor), while her dog is standing by peering up at her. Meanwhile she is talking on the phone with Dr. James Levine, who she says is the “leading researcher in the marvelous-sounding field of inactivity studies.”

Levine claims we spend all too much time sitting somewhere, making use of a chair or sofa, not moving about or even standing. He reports that people who stayed thin were able to greatly increase their overall activity rate (fidgeting, pacing, standing, bouncing, or jiggling their legs) compared to those prone to gain weight.

According to Orlean, investigators have reported that individuals who sit for six hours or more each day have an over-all death rate twenty percent higher than those who sit for three hours or less, while walking (distance or time or number of steps was not reported) reduced the risk of cardiovascular problems by thirty-one percent and cut the risk of dying by thirty-two percent during the period of the study.

“The worst news,” she says,” is that hard exercise for an hour a day may not cancel out the damage done by sitting for six hours.” Can this really be true?

The treadmill desk seems a totally fanciful idea to me. I can’t imagine concentrating on my work or even emailing someone, while walking slowly. Orlean estimates there are now more than a thousand members of a group who work at a treadmill desk.

The practice is not exactly sweeping the nation, but her article does suggest that remaining inactive most of the day may have ill effects that haven’t been widely recognized before.

In an article in the New Yorker, the always-amusing Susan Orlean claims that sitting most of the day can cancel all the benefits of exercising for an hour or so of daily exercising. I always thought that being fit and healthy was simply a matter of frequent exercising. No, she says, non-exercise activity is far more important.

Here she is writing the article while walking slowly on a treadmill, typing away on her “walking desk.” The treadmill sits below an elevated platform with her computer screen and keypad, printer (on the floor), while her dog is standing by peering up at her. Meanwhile she is talking on the phone with Dr. James Levine, who she says is the “leading researcher in the marvelous-sounding field of inactivity studies.”

Levine claims we spend all too much time sitting somewhere, making use of a chair or sofa, not moving about or even standing. He reports that people who stayed thin were able to greatly increase their overall activity rate (fidgeting, pacing, standing, bouncing, or jiggling their legs) compared to those prone to gain weight.

According to Orlean, investigators have reported that individuals who sit for six hours or more each day have an over-all death rate twenty percent higher than those who sit for three hours or less, while walking (distance or time or number of steps was not reported) reduced the risk of cardiovascular problems by thirty-one percent and cut the risk of dying by thirty-two percent during the period of the study.

“The worst news,” she says,” is that hard exercise for an hour a day may not cancel out the damage done by sitting for six hours.” Can this really be true?

The treadmill desk seems a totally fanciful idea to me. I can’t imagine concentrating on my work or even emailing someone, while walking slowly. Orlean estimates there are now more than a thousand members of a group who work at a treadmill desk.

The practice is not exactly sweeping the nation, but her article does suggest that remaining inactive most of the day may have ill effects that haven’t been widely recognized before.

3.03.2014

The Great Beauty

The Great Beauty, winner of the Academy Award for the Best Foreign film of the year, is a treat, a film of visual riches, the riches of Rome, wild parties, melancholy reflections. None of it is true in the literal sense. It is a trick of the imagination, homage to another trickster, Fellini. But like all tricks, its deceptions have an element of truth in them.

The film is the story of a 65 year-old Jep Gambardella (played by Toni Servillo), who wrote a popular book some time ago and has never written another. He has a gorgeous apartment overlooking the Coliseum with a terrace where he gives his parties for the beautiful people of Rome that last all night and well beyond the morning sunrise.

There is exuberant dancing, absurd conversation, drinking, an overload of sensual riches that never stop. Jep wanders around the streets of Rome, watching, reminiscing, meets a friend, lingers in art galleries, and goes to another all night party, where there is more drinking, beautiful women, hypocrisy and boogie-woogie.

A reviewer writes: “Never have cynicism and disillusion seemed more intoxicating that in The Great Beauty.” That captures the spirit of this film perfectly.

Then a friend comes to visit Jep, informs him his wife died, that she only truly loved Jep, after an early romance between them. It is all written in her diary, unlocked after her death. The film takes a turn toward the solemn. Jep asks to read the diary. Her husband isn’t offended but says that it’s not possible, as the diary was thrown away.

I wrote to a friend who lives in Rome that I was going to see the film. From what I had read, I thought it would be a love letter to Rome. She replied:

Well, the Great Beauty does not at all represents Rome, I mean the reality described by the film is absolutely present, it is the image of a social class deeply present in Italy and it is the one which ruined our country because links politics and its power with private interests. However, Rome is magic, I travel a lot ... but Rome has something special, something that keeps you company also when you are alone. Everywhere you see there is art, the past and its traditions wraps you.

I left the theater in a daze, but unimpressed, not knowing what to say about it or what is worth thinking about. Jep had spent his life searching for the great beauty and never found it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)