As his hearing grew weaker in the years ahead he felt more and more isolated, trapped in an incompetent body, foolish and pathetic.

Andrew Motion

A few years ago, I noticed I wasn’t hearing as well as I used to. I didn’t always catch the questions my students were asking in large lecture classes, nor was I hearing much of the chatter on television with the same volume setting I always used.

Eventually the problem grew somewhat worse and I tried using tiny digital hearing aids. I found them disappointing, as I no longer sounded like myself, they amplified too many unpleasant sounds, and they were useless in a social situation with a fair amount of background noise. Hearing aids do not accomplish for the ears what glasses do for the eyes.

In time, I began to appreciate the new auditory world that I lived in. Closed captions on the television made hearing largely unnecessary and that was the same for the subtitles in the films I preferred. And when I went to the theater or to an English language film, I could usually obtain a wireless audio amplifier, if I wanted one.

My world became less noisy, the roar of the traffic didn’t bother me, and the overall quietude appealed to me. So did observing all the non-verbal cues of human behavior that I usually didn’t pay much attention to and yet often conveyed as much meaning, if not more, than spoken words.

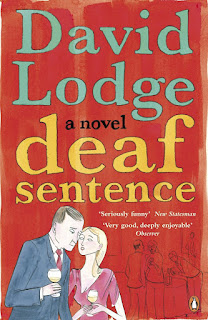

My views about this new auditory world, differs from David Lodge’s expressed in Deaf Sentence. He writes: "Deafness is a kind of pre-death, a drawn-out introduction to the long silence into which we will all eventually lapse." Lodge had to give up teaching and greatly missed “the rhythm of the academic year.” However, I believe his hearing loss was far greater than mine.

As my social world narrowed, I began to wonder about the consequences of the limited number of conversations I have. There are days when I speak to no one, whether in person or on the phone. So I turn to the research to find out and am not surprised by the conflicting results. I look more closely at the studies to try to determine the most rigorous. It is impossible to identify them.

Absent that, I turn to those solitary souls who I most admire and here I see no change in their talent. I think of Beethoven who wrote his 9th Symphony when he was deaf. He said:

"Yet it was impossible for me to say to people, 'Speak louder, shout, for I am deaf…But what a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone standing next to me heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing.”

I do find it embarrassing when I turn down invitations to social gatherings where it is usually impossible for me to hear the speech of the person I am sitting next to. What can I say when a person talks to me? “Could you speak louder?” “Would you mind repeating that?” No, I say neither of these things. Instead I mumble something back and hope that I will not be thought deranged.

Beethoven was similarly embarrassed:

"Forgive me when you see me draw back when I would have gladly mingled with you. My misfortune is doubly painful to me because I am bound to be misunderstood; for me there can be no relaxation with my fellow men, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of ideas."

In her Paris Review interview, Marilynne Robinson, who lives a largely solitary life, commented:

"… I go days without hearing another human voice and never notice it. I never fear it. The only thing I fear is the intensity of my attachment to it. It’s a predisposition in my family. My brother is a solitary. My mother is a solitary. I grew up with the confidence that the greatest privilege was to be alone and have all the time you wanted. That was the cream of existence. I owe everything that I have done to the fact that I am very much at ease being alone. It’s a good predisposition in a writer. And books are good company. Nothing is more human than a book."

1.24.2013

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)