I am reading. I come across a sentence or a phrase that stops me in my tracks. I read it again. Something about it hits me—a question, conjecture, a bit of truth, sometimes a truth about myself. I put a parenthesis around it and note the page number on the inside back cover of the book. And when I finish the book, I copy all the saved passages into a Word document and add them to my Commonplace Book.

I am reading. I come across a sentence or a phrase that stops me in my tracks. I read it again. Something about it hits me—a question, conjecture, a bit of truth, sometimes a truth about myself. I put a parenthesis around it and note the page number on the inside back cover of the book. And when I finish the book, I copy all the saved passages into a Word document and add them to my Commonplace Book.The passage is part of the story. But that isn’t why I mark it. I do that because it is relevant to me that may or may not have any relevance to the tale. Another reader might also mark the passage but for entirely different reasons. Or not mark it at all. Instead she marks other passages that I quickly pass by.

Recently I bumped into Fluther, a question and answer website with a social twist. Twitter recently purchased the company that runs it. I must have found it by doing a search for underlining or highlighting passages since it was the subject of the question that appeared on my screen: Do you underline passages in books when you are reading them?

To date fifty-three individuals have described the way they do or do not write in the books they are reading. One person answered, As I read a book, I often underline or highlight passages that I find interesting, things that I can relate to, or words that are really insightful. When I re-read some books, I often reconnect with these passages instantly, but sometimes I find them odd, and wonder what state of mind or stage in life I was at when I first underlined them.

Another person confessed, I’ve always felt that it was wrong to write in books. I know lots of people do it, and many great authors and thinkers have done it, but I just can’t bring myself to write in my books, whether textbooks, novels, or non-fiction, I just can’t do it.

One reported she often bought an extra copy of a book that she had marked up, if it was one she really liked. However, no one said they took the extra step of saving their highlighted passages in electronic form, as I do.

I often ask myself why have I been saving the passages that I mark in books. Is it simply a mindless habit? Yes, I return to them now and then. However, rarely if ever do I return to a single passage and write about it. Nor do I organize a set of passages from various books that deal with a single theme. It would be good to that.

And whenever I return to the collection of passages in my Commonplace Book and open it to a randomly selected page, I am amazed at how provocative many of them are and it is almost a crime to leave them there without some kind of additional commentary or review.

Sometimes saving these passages helps me to remember the book and think once again about its story and themes. So in this way, saving them becomes a memory aid. There’s no other way I could possibly remember the books I read or the ideas in them, without saving them electronically and then printing the collection at the end of each year.

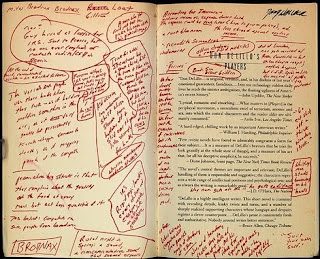

Recently Patrick Kurp wrote on his blog, Anecdotal Evidence: For years I’ve kept notebooks in which I transcribe notable passages from my reading. These commonplace books used to be almost random, organized only by chronology, but they grew unwieldy because I never found time to devise useful indexes. They were diverting to browse but almost worthless if I sought a specific passage or topic.

The fact that saving the passages electronically permits such a search is one of the major reasons I spend the extra time copying them. It is a highly effectively way to create the kind of index that Kurp seeks. He also experiences the same thing I do when I return to read some of the passages I’ve been saving all these years. It is sometimes rather startling.

At some point I started dedicating discrete notebooks to large subjects – Trees, Birds, I’ve leafed through it the last several days, marveling at the amount of insight and first-rate writing devoted to the subject, the central event in our history, the one we’re still contesting. For a sobering insight, compare the mass of words inspired by the Vietnam War. Michael Herr? Tim O’Brien