“All our knowledge results from questions, which is another way of saying that questioning is our most important intellectual tool.” Neil Postman

In addition to the role of question in works of fiction, I have noticed it is also a feature in the way individuals talk with one another. Some ask a great many questions, while others might ask one or two and, more commonly, none at all. I sense that questioning as a mode of conversation, indeed, as a way of thinking, may be a central personality dimension.

My hunch is that it is strongly associated with a philosophical turn of mind, a general skepticism about most beliefs and assertions, at least, a continuing effort to look more deeply into the claims of others whether they are expressed in conversation or the printed page.

Katherine Mansfield was another writer who championed Chekhov precisely because he had no answers to the existential questions he poses. In a letter she sent to Virginia Woolf about Chekhov in 1919, she writes: “What the writer does is not so much solve the question but…put the question.” From the Introduction to Anton Chekhov’s About Love and Other Stories by Rosamund Bartlett

In contrast, other individuals seem more accepting of whatever it is they hear or read and tend to comment, if they say anything at all, with a “That is really interesting” or “It reminds me of this or that” or simply change the subject altogether. They are unlikely to express any doubts or seek clarification or evidence especially contrary evidence, relevant to the matter at hand.

Those of the questioning frame of mind use an approach not unlike that of a Socratic dialogue where conversation becomes a progression of questions designed to arrive at a conclusion beyond the originally stated position. Some people feel very comfortable with this kind of discussion. For them it becomes a truly joint exchange with the implicit goal of clarifying thinking and sharpening beliefs and perhaps even learning something along the way. In contrast, those of the accepting frame of mind do not fall naturally into this conversational mode and may find it difficult to talk with someone who does.

Questioning is also a critical element of the Jewish tradition. The Talmud, for example, is structured around a set of questions that are in turn answered by fresh questions. Responding to a question with another question is also a well-known Jewish practice.

“Asking questions is both the secret of science and the essence of the Talmud, the dialectic forming character of the Jewish people.” “The act of learning is the central pillar or backbone of Judaism.” Rabbi Adin Steinsalz

When questions are posed in a work of fiction, they are rarely answered, nor do they really have any clear-cut answers. But what the author does intentionally or not, is lead the reader to consider the questions and begin wondering about them. At least that’s what happens to me.

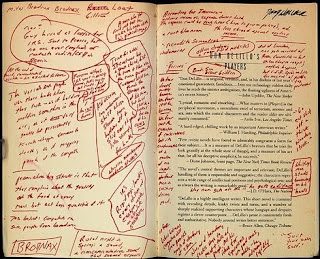

And when it does, I become more engaged with the text and begin to make all the associations that come with my experience and previous knowledge of the subject. I don’t rewrite the story, but may embellish it a bit. In a way, I join with the author who, with his questions, invites me to participate with him in telling the story. It is a highly desired reading experience.

“I tend to like questions that go unanswered in general because they invite me to think. And since there is no answer provided by the “expert” there is also no completely right or completely wrong response which gives me room to really think and possibly be wildly creative about it. That’s much more fun than being fenced in by someone else’s answers and then spending all my thinking time figuring out those answers don’t work for me…” Stefanie Hollmichel http://somanybooksblog.com